Originally published on Marci 6, 2014 on Pepper. Words by me, photos and text editing with additional reporting by Lars Roxas. Photo editing by Mylene Chung.

It started with a joke. At least, I thought it was a joke.

I was late for a good friend’s party. I had missed the singing of the birthday song and the blowing out of the candles, but there was still a lot of cake. My friend cheerfully offered me a slice. “Would you like cake from Bilibid?” she asked. I didn’t believe her, being used to bouts of irreverence from my friends, but I did accept the cake.

She sliced me a piece from the spongy golden cake, its sticky yellow icing glistening under the flourescent light in their dining room. I was surprised at how fluffy it was. If she hadn’t said anything, I would have thought they’d bought it from a direct order baker. “No, really,” she insisted, “Bilibid.”

“How did you get this cake from there?” I asked. Little did I know that the answer would lead me from the comforts of their home to the Maximum Security Compound of the New Bilibid Prison.

My friend’s father, Zeno, a thin, talkative man in his late forties with moles on his face, was the one who ordered the cake for his daughter. He offered to take me to Bilibid for a visit so I could see for myself where it came from and meet the people who made it. He filed the necessary paperwork a week in advance, a visitation request signed by our ad-hoc hosts, inmates Michael Alvir and JV Medalla from the Maximum Security Compound. Zeno works closely with Alvir and Medalla as a civilian volunteer for different social development programs within the compound. In the past, he had also occasionally handled orders and deliveries for their bakeshop’s civilian customers.

“It’s a bakeshop, not a bakery,” he corrects me.

Bilibid as I imagined it, from the trailers of Filipino action movies I saw as a kid, was made up of large dimly lit rooms with makeshift dining areas on rickety chairs and tables. Cramped quarters curtained by thin cloth, grills on the windows, with roving guards tapping the gun on their holsters while swinging a heavy stick with their other hand were the images I had in my head. An oven, a counter, and kitchenware did not fit into any of those scenes.

I, along with my editor Lars, who was playing photographer that day, joined Zeno during one of his courtesy calls one Saturday morning. The stories he shared of his time with the program were surreal, absurd even, punctuated with good-natured laughter on the road from Magallanes to Muntinlupa. One of his main projects within the prison involved holding and managing events. One event he hosted was the Bilibid Iron Chef competition, a simplified version of TV’s popular Iron Chef franchise. Groups within the compounds were challenged to put together a three-course meal based on a surprise main ingredient.

“There was this one man, he was very good with the knife. He could chop really fast,” Zeno told us. “I wanted to interview him but when I asked the guard what he was in for, the guard told me he was one of the suspects for the Laguna massacre case.”

Another member of our little band was Doc Cathy, a medical professional who lives in the BF Homes area. As a licensed doctor, Doc Cathy helps Zeno with medical missions for the prison community. She also taught Zeno a shortcut to Bilbid from BF through Katarungan Village, shaving at least an hour stuck in traffic from our travel time.

As we drive further away from the familiar, the smattering of tiny restaurants, shops, and salons that make up BF soon faded from our view. The streets smoothed out, obviously freshly paved, and large empty fields filled the space between buildings. We entered the gated village of Katarungan. From the name, even with it’s upper middle class exterior with large houses and satellite dishes all around, it was clear that it meant to cater to those who wanted to be near the prison. “Bilibid,” Zeno tells the village guard manning the gate and pays the thirty peso toll to let us through. The village is quiet for a Saturday, seemingly empty if not for the occasional kid or man on bike passing by.

Soon came bumpier roads. There were more trees, and a number of sari-sari stores whizzed by. Finally, we catch sight of Bilibid’s iconic façade, built to look like a white castle gate. We had arrived.

“We’ll take pictures there later,” Zeno said, referring to the landmark. He parked by the side of a large field where a number of kids played catch while adults watched. As soon as we step out, a buko salad vendor with a large styrofoam cooler stops, offering us his wares. I see a cluster of buildings around the corner, with a long line of people snaking away from the solitary entrance.

Before our trip, Zeno had given us a quick run-through on the do’s and dont’s of visiting the Maximum Security Compound. Girls are not allowed to wear sleeveless shirts or shorts. Absolutely no cellphones, tablets, or any kind of gadget that can transmit beyond the walls are allowed. You can’t bring in rubbing alcohol, drugs, and of course, you can’t wear orange shirts.

“When you bring food, they’re carefully inspected. Even with lechon, only certain parts are allowed inside. They have to make sure they aren’t used to smuggle drugs in or out,” explains Zeno as we cut ahead of the line, invitation letter in hand. That letter was our golden ticket inside. One quick glance and a whispered word was all it took for the guard to allow us in.

Our first stop was baggage inspection, right outside the receiving area. All bags had to be placed on the floor to allow a K9 unit to inspect them for contraband. Doc Cathy and I put our bags down and stepped back. A woman behind me, with dyed hair and wearing branded sunglasses and tight jeans, puts down an expensive designer bag without complaint or hesitation. She’s obviously been through this before.

Visitors that day were mostly women with kids in tow. While we waited for the K9 to come out, a guard would occasionally pop in and out of the doorway to the receiving area. “Priority guests!” he called. Sometimes one man, sometimes entire families, would then step up to answer his call. An older woman next to me, struggling with her large bayong of food, grumbled at the seeming injustice of the priority guest call. There were murmurs among the other visitors, recognizing some of the names being called out as belonging to this or that notorious drug lord.

While we waited, I studied a more detailed list of rules and regulations for visitors posted on a nearby wall. In addition to the things Zeno had already told us about, there were also rules against bringing in petroleum jelly, yeast, and movies that depicted criminal violence and drug dealing. The first two made sense, the last, was harder to puzzle out the reason for.

One large guard with a bouncer’s frame ushered all of us to the opposite side of the inspection area. “Clear the way! The dog bites!” he called out in Filipino, over and over again, “He has a nasty bite! Clear the way!”

A large brown labrador trotted out. It gave each bag a quick sniff before moving on. As soon as all the packages were cleared, there was an immediate stampede for the bags. Lars found the whole thing oddly reminiscent of concertgoers rushing the stage the moment the band starts playing.

“They sometimes smuggle drugs and cellphones in the body’s cavities,” Zeno explains as we go through another round of inspections. A guard patted us down, inspected our shoes, and did another check of our bags. To the guard’s left was a pile of confiscated rubbing alcohol from previous guests. “But I wonder what happens when the cellphone vibrates?” At his quip, the guard gives a chuckle.

We take our bags and move to the third and final inspection. Males and females are separated into two areas, opposite of each other. The lady guard patted around my chest and waist area while she attended to family members calling on her bright pink cellphone. Satisfied I wasn’t hiding anything under my bra, she signaled me to move on to the exit. We had made it through, at last.

We step out, to another tunnel, but this time outdoors, with high concrete walls fencing us in to the left and right and barbed wire crisscrossing over our heads. We were drawing near the compound itself.

“Do you want to know what it’s like to be Imelda?” Zeno asks me as we reach the end of the tunnel. I didn’t understand that joke until we get to a large plaza at the end of our path. A crowd of men in orange, some riding pedicabs and others holding umbrellas ushered for us to go to them. Zeno invokes Michael’s name and picks out five from the throng to escort us. Each went up to our side, opening their umbrellas to protect us from the sun. I got the joke.

“Here we go,” Zeno, and we walked deeper into Maximum Security Compound as the noontime sun began to rise. A white arch ahead welcomes us, and an older man in orange calls out, “BCJ, BCJ, they’re with BCJ!”

Michael Alvir, called Mike by his companions, is the first to meet and welcome our little group. At the Bilibid Re-Education Center, a small concrete structure with whitewashed walls, we are greeted by Mike and his family. They are just about to have lunch and we were asked to join them. With his glasses, fair skin, and educated diction, Mike is not the stereotypical Bilibid inmate. His two sisters, Marga and Keira, his Mom, Bella, and his girlfriend accompany him.

Stoic inmates attended us, arranging the chairs and tables, and serving us drinks. As we started eating, a sumptuous spread of, unexpectedly well cooked, tinola and pritong tilapia, Mike urged them to join us, but they shyly declined and kept to themselves at another table. The mood at the table was light, Mike encouraged us to take as much as we wanted, quipping that it’s always “unli-rice” here inside Bilibid’s walls. We asked him about life inside the prison, and he did his best to answer all our questions.

After lunch, we cleaned up to make room for another volunteer group holding group sharing sessions with the inmates. They talk to select prisoners of Bilibid, asking them what, if anything, had made them happy since the last meeting. As a new session begun, we quickly exited the Re-Education Center to follow Mike. He was going to introduce us to the person responsible for the Yema Cake.

The person we’re due to meet, the proprietor of the bakeshop that we’ve come to find, is JV Medalla. He’s been imprisoned in Bilibid for the last several years, one of ten incriminated in a high profile case from the nineties involving a clash between two fraternities that ended with an accidental fatality. They swear by their innocence, and their case has bounced in and out of appeals court ever since. JV and the rest of his brads were first held in Quezon City Jail, before being later moved to Bilibid following their conviction. While inside, they became members of Batang City Jail (BCJ), one of the oldest and most recognizable prison jail gangs in the country.

It’s somewhat true what pop culture says, people join gangs for protection in a hostile environment, and there’s precious few places more hostile than the dog-eat-dog world of prison. More than that, the system tolerates the existence of gangs as they help keep order among the inmates. Gangs are a way for prisoners to govern themselves and keep discipline, allowing the formation of boundaries, as well as providing a more “peaceful” avenue to resolve disputes, more peaceful, in any case, than a full-blown gang war.

While far from a perfect system, it works. Zeno swears that in the four years he’s visited Bilibid, he has never witnessed a prison riot. If anything, he finds that prisoners would rather cooperate with each other to keep what few privileges they have, such as overnight visits from loved ones and regular meals, than risk a total prison lockdown over some minor clash.

JV, like Mike, is considered a leader in Bilibid’s Batang City Jail, called Mayor by the inmates. As both had the privilege of a college education, and the connections such an education implied, they sought for ways to stay productive while waiting out their time. They also wanted to find a way to uplift the day-to-day lives of their fellow inmates. In the few minutes we’d walked under the hot sun, we’d passed by a row of sari-sari stores, a number of karaoke machines, and several eateries. Clearly, something is working.

Our meeting place was the BCJ plaza. From the inmates own money, they’d built an impressive facility in the heart of their territory inside Bilibid. They had a park, an events stage, a tennis/basketball court, and even a mini zoo. The latter contained several attractions, Philippine eagles, a large snake that was either sleeping or dead, and two docile monkeys named Moymoy and Maymay. As Lars snapped pictures of the friendly primates, they stopped what they were doing and looked straight at the camera, not moving until Lars was satisfied with the photos. This amused a nearby inmate, who called out in glee, “Moymoy knows how to pose!”

We sat by the court as we waited for JV, watching tattooed players play a spirited game of tennis. A few minutes later, JV joins us, flushed from the hurry. “I’m so sorry I’m late, I was just attending to some things,” he says. We’re introduced and exchange names and handshakes. “My voice is hoarse! We had a basketball tournament this morning, I was asked to coach last minute.”

JV sends out for coffee from one of the inmates, and as we wait for our hot drinks to arrive, he regaled us with the story of the exciting basketball game he’d coached earlier. It was a match between Batang City Jail and Sigi Sigi Sputnik, a rival gang who controlled a quadrant of their own in Bilibid. Stakes are always high whenever rival gangs face off, even if it’s in events such as sports. According to him, the entire plaza was filled with spectators from both sides cheering and jeering the teams on while the guards kept close watch, guns at the ready. He points to the scoreboard nearby. Batang City Jail won in overtime by just two points, 106-104.

One happy fan won two hundred thousand pesos betting on the home team, we thought it wise not to ask where inmates could possibly find that kind of money on the inside.

Microbusinesses such as sari-sari stores and drink stands are allowed inside the compound. While bringing in cash was largely discouraged, it was not banned, unlike in other correctional systems abroad. Even behind bars, most inmates still needed to earn a living for their family. Once or twice while waiting for JV, we were approached by prisoners selling various homemade curious, from bamboo art, to jewelry, to a bag of homemade pastillas.

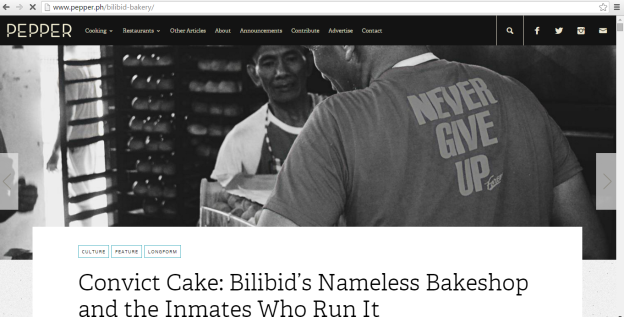

JV was the one who thought of putting up the bakery as part of a livelihood program to help inmates earn for their families outside. He set it up with the help of Romeo Jalosjos’ Lamb of God Foundation, and a friend of his who was a pastry chef from a top international hotel in Manila. The chef trained the inmates and taught them how to bake everything from foccacia, ciabatta, and baguette to cakes, ensaymada, and pandesal.

“The European breads aren’t very popular,” says JV. “The foreign inmates like it, but it doesn’t sell as well as the monay and pandesal.” His best customers after all, are inside the compound. “It is a captured market.” He says without irony, as any businessman would. The bakeshop runs with permission from the prison warden, and they source practically all their ingredients from an internal Co-op run by the Bureau of Corrections.

Since it opened for business, the bakeshop has helped sixty scholars, family members of those in the prison, finish their education. More importantly, it gives the inmates a positive outlet while at the same time imparting skills that they can use should they finally be freed from the confines of the prison.

When the bakeshop was first set up in 2006, word got around. It saw some success, and even became the sole supplier of bread for all of Bilibid for a short while. Neighborhood bakeries from the outside even ordered from them for resale. Certain complications within the system and the envy of a rival gang, however, saw the bakeshop seized from their control a number of years ago. JV has only recently won it back, though he was dismayed at the sad state of the equipment upon his return. It has been a year since it has started operations back again, and JV hopes to gain back the same following he had before.

The bakery is now part of a nameless carinderia inside the Batang City Jail Plaza. It’s one large structure split into two, one side for the carinderia and the other for the bakeshop. A dozen tables line the dining area, some inside with several more outside bordering the plaza. The bakeshop employs about a dozen inmates as bakers, with several more handling the counter, keeping track of the stock room, and working as the bakeshops vendors in other quadrants of Bilibid not under the control of BCJ.

JV points to one baker, who was expertly breaking a thick line of dough into smaller, palm-sized balls, “That will be pandesal.” He explains. “That’s something we’ve learned from years of baking, an exact measure for one pandesal.”

While they baked, not a smile was cracked by any of the workers. For a largely informal bakery, with no head baker in sight, there is little to no chatter. The floors are clean, without a single thing out of place. They wore aprons, and even hairnets to keep their hair in place. They worked like a well-oiled machine, from mixing the dough, rolling and shaping, laying them out onto baking pans, then sticking them into one of the industrial-sized ovens inside.

“The last group, when they handled it,” sighed JV, “Didn’t take very good care of our equipment. I had to replace some parts, throw away the others, sayang – too bad.” He points at one unused machine near the doorway, “See? I used to sell soft-serve ice cream in different flavors.”

I had ordered a Yema Cake to review for Pepper, the same cake I first tasted at my friend’s birthday party. It was already boxed when I came by to pick it up, in red and white cardboard. He lifted the lid to show off the chocolate icing embellishments on the corners and the sides, “Are you sure you don’t want to have anything else written on it?” he asked.

On one wall in the frosting area, are several post-it notes, with happy birthday greetings and names underneath. The outside orders have started coming in again, much to JV’s relief. They can accept orders about a day in advance, and have it ready for pick-up or delivery through any of their suppliers.

I had joked to a friend before my visit, that perhaps after a trip through their bakery, I would know better than to order from them again. All my negative assumptions were proven wrong.

After the tour, we head back to the hut by the tennis court for coffee. We pass by Mike and his family in front of the bakeshop, who were in an excitable discussion. An inter-Bilibid volleyball tournament was coming up, and there was a competition for best muse. Muses can be hired from outside. If the gang had the resources, even quasi-celebrities and “models” from local adult magazines had in the past been known to make an appearance. For the next tournament, Mike was trying to convince Marga, his little sister, to represent BCJ, “It’s just for one day,” he pleaded. “We’ll find ways to get your hair and make-up done. Let’s do cosplay, something different, something that stands out from the other muses…”

Not far from where we were, a larger building with rows of small windows and thick grills loomed over the plaza, a reminder that everything around us was a privilege. While JV’s tale was simple, and sounded not too different from the struggles of any small business with big dreams, its not often one encounters competitors from the outside who are literally out for blood.

Since it was a weekend, and families are allowed to visit on weekends, we were surrounded by other civilians with not a guard in sight. Our stay had the illusion of normalcy, like were merely on a day trip getaway. Yet in one instance, mere minutes as our guides attended to other things, that cold feeling of dread, of being watched without anyone looking—or caught looking—came over me. This was safe, but only for now. There were numerous little things that caught one’s eye, whether it’s Mike sending an escort for his family whenever they left for the bathroom, or the near altercation that occurred when an inmate carrying coffee accidentally spilled some on one of his superiors. The inmate was quickly ushered away, and was not seen for the rest of the afternoon.

“Life is simpler here,” observes Zeno, “You don’t pay taxes. You’re fed. You don’t worry about earning.”

“But you’ll never know.” JV says. “One moment the old man you’ve shared laughs and bonded with the day before is okay, and then suddenly he’s carted off before you dead and stabbed all over. You never really know.”

Still, JV tries to look on the bright side. “I was nothing outside. I never got to meet celebrities” JV laughs, “While here I’ve been up close with Sharon Cuneta, John Lloyd Cruz, Rivermaya, and all these other stars.”

It was one of the last few things he tells us before we say our goodbyes and are escorted out of the prison. We head out, back to the welcome plaza, towards the door that would lead us back down the long white hallway to freedom.

“He’s doing better now.” Zeno tells Doc Cat and I as we walk back to the guard table for our IDs. “Now he has something to look forward to. Before that, he was depressed.”

We make our way back to the parking lot, to the car. I breathe a sigh of relief as I retrieve my cellphone, hidden under the passenger car seat. We have been gone for four hours. It felt like a whole day. The sky was a bright pink, and the sun was starting to set. A different set of kids are playing in the field.

Simple as life looks like on the inside, it’s the little things that make all the difference, that you’ll miss the most from beyond the walls. The choice of where to go next, where to stop for dinner, or where to get down to catch our ride back home, all seemingly minor decisions that are so easy to take for granted. Even the choice of what color of clothes to wear would mean so much to someone who has seen nothing but white and orange for the last several years.

In the meantime, they wait. They bake cakes. While they hope, however in vain, they at least find a little comfort in the crumbs.